By

Semra Eren-Nijhar

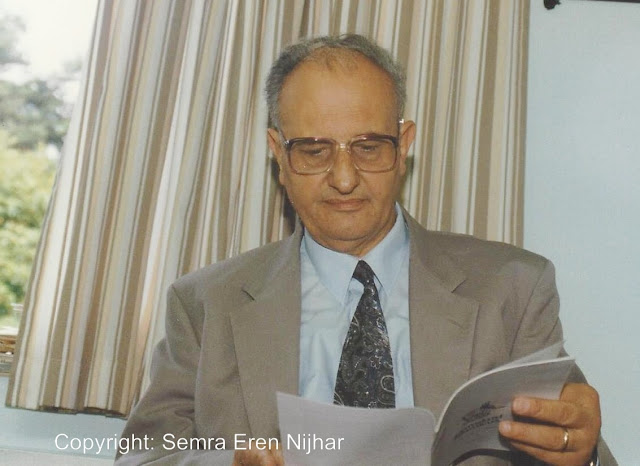

“I took early retirement to concentrate on my

research and writings” said Prof. Salahi Sonyel, who sadly passed away on

Christmas Day 2015, in an interview I had conducted with him back in 1998. And

indeed his writings and all the research he conducted over many years made him

one of the most respected Turkish Cypriot historians residing in Britain

Prof.

Sonyel was born in Cyprus in

1932 and graduated from the English School in Lefkoşa (Nicosia

He

first came to Britain in

1957, studied at the Queen's University, Belfast Cyprus and then returned to the UK in 1964 following the start of the troubles

in Cyprus UK

In

1971, he gained his PhD from the University

of London and became an Associate of the Institute of Education Europe .

|

| Prof. Sonyel was a lifelong member of Cemiyet, located in D'Arblay Street |

As a historian he was an expert on

Atatürk, Atatürk’s revolutions, Turkey ’s

Independence War and the period during the establishment of the Republic of Turkey Turkey Ankara

After

our first meeting in1998, I met Prof. Sonyel on many occasions and interviewed

him on various different other subjects. On areas such as migration, identity,

racism, and being Turkish and living in the UK

Soon

after I met him, I learned about his research in the area of Turkish migration

while he was active in the Cemiyet during the

1970s and 1980s. I discovered fairly quickly that he was interested in the

education of Turkish and Muslim children in schools, and had written many

articles about their situation along with education improvement strategies. His

book The Silent Minority – Turkish Muslim

Children in British Schools, published in 1988, widened the debate within

society on the underachievement of Turkish-speaking children in British schools,

which remains a challenge even today.

To

my surprise, I went on to discover the immense work he had carried out in the

area of the Turkish people living in Britain

In

one of our conversations Prof. Sonyel told me he had originally wanted to

become a poet and wanted to work in the area of literature, something he was

very passionate about. However the Turkish Cypriot poet and writer Nazif

Süleyman Ebeoğlu said to him at the beginning of the 1950s that Osman Türkay

will become a very famous poet, but he (Prof.Sonyel) should rather concentrate

his energy on other areas like political science, economics or social sciences. Nazif Süleyman Ebeoğlu’s advice was to prove

very wise and helped Prof Sonyel to find his own way into the world of social

sciences. He was very grateful to Nazif Süleyman Ebeoğlu, whom he considered

his teacher and mentor.

Prof.

Sonyel also worked very closely with the twice Nobel Prize Nominee Turkish

Cypriot poet Osman Türkay, helping him and other members of Cemiyet with the publication of their

magazines. Innovative papers and articles were published on the issues faced by

ethnic minorities, which were unique and groundbreaking during the period,

especially in the 1970s where people were seemingly more interested in talking

about the migrants’ issues instead of analysing and writing about them. I have

not yet come across in any periodicals which were published during the 1970s by

any other ethnic minority communities concerning the issues faced by migrants

during that era.

Prof

Sonyel was aware of the existence of racism in British society and worked

tirelessly to overcome the prejudice in the wider community. He told me in one

of our conversations: “When I first came

here, I tried to find employment, but found it very difficult because of my

name, as it is a Muslim name. I changed my name and within a fortnight I became

the head of a large social science department in a secondary school. I changed

my name when racism was rampant in the

Prof

Sonyel was aware of the existence of racism in British society and worked

tirelessly to overcome the prejudice in the wider community. He told me in one

of our conversations: “When I first came

here, I tried to find employment, but found it very difficult because of my

name, as it is a Muslim name. I changed my name and within a fortnight I became

the head of a large social science department in a secondary school. I changed

my name when racism was rampant in the

The modern day term

‘Islamophobia’ seems to have existed in different guises much before the 9/11

events.

In fact it is shocking to know that a

respected historian and academic had to change his Muslim sounding name in to

an English sounding one, in order to progress within his profession and

professional life. It is important

to mark the current atrocities happening in the name of Islam and increased

Islamophobia in British society, yet we must also remember that Islamophobia is

not an entirely new issue.

Prof. Sonyel reminded me in some of

our interviews on this subject that, the level of racism is not the same

as that experienced by Asian or Black people living in Britain

Prof.

Sonyel will be remembered not only as a historian, but I believe it would be

improper if we failed to recognise

him as a social scientist too. It would be unforgiveable to forget all the work

he has done in the last 50 years, in the area of exclusion, xenophobia,

education of Turkish-speaking children and Turkish migration to Britain

|

| In 2002, Prof. Salahi was awarded the State Medal for Distinguished Service by Turkish Foreign Minister Ismail Cem |

Prof.

Sonyel was one of many remarkable people from the Turkish-speaking community

who came to Britain , stayed,

lived and worked in Britain

He

worked very hard and crafted his thoughts into words, the words were converted

into books; these books will, in the future, be converted into new thoughts.

Prof. Sonyel left a written historical legacy for the future generation of the

Turkish-speaking communities not only in Britain

He

once remarked, “I live in Britain

Prof. Sonyel has published many

books, articles and pamphlets. Some of his books in English are Atatürk – The Founder of Modern Turkey ’, Minorities and The Destruction of The Ottoman Empire , and The Assyrians of Turkey Victims

of Major Power Policy. His works appeared in numerous periodicals and newspapers in Cyprus , Turkey ,

Greece , UK , the United States

|

| Some of Prof. Salahi Sonyel's many publications |

He

was a visiting professor at the Near East University in Lefkoşa, in the Turkish

Republic of Northern Cyprus , as well as in various universities

in Turkey , Britain

Prof.

Sonyel became a major part of the history of the Turkish people living in Britain and also played a huge role in recording

history and sharing his analysis of the Turkish people living in the UK

He

was married and had two daughters.

No comments:

Post a Comment